Lire en français

Published on 14/06/2012 | Updated on 05/03/2026

Abstract Timeline Process Method Postcards Albums Press

« Environment is important, games are very geographical – they present space almost better than they present time, and we try to use that, to showcase variety between different landscapes. It’s this idea of a digital holiday: being able to explore spaces that don’t really exist is one of the things that’s fascinating about open world games. It’s not just about doing the activities we’ve set, there’s also a sense of being there. » Dan Houser, Rockstar Games (source)

The new boundaries of cyberspace

Virtual Tourism is a series of photographs, videos and logbooks, based on the contemplative practice of gaming, allowing tangible memories of virtual travel to be preserved – also known as In-game photography or Virtual photography. Over the years, this project has evolved into a writing project, recounting the joyful and gradual immersion of a little geek from Western Europe into the new territories of cyberspace. A testimony that attempts to describe the impact of digital worlds on our psyche and their implications in our real world.

Project timeline

The 1980s and 1990s – First wonders

Like many young geeks in Western Europe, I experienced a rather classic and happy period of wonderment with video games. After school, homework, adventures with friends in the park or in the forest of Fontainebleau, music theory, violin, gymnastics or karate lessons, we were allowed to watch films, television or play video games. In arcades, on NES and Super Nintendo, to begin with. Then came my cousin’s Amiga and our parents’ first PC, on which I experienced my first frights in a virtual world in Alone in The Dark; my first immersion in a cyberpunk universe in Syndicate; and my first dive into a world of poetic digital adventure in Little Big Adventure. Too demanding on hardware resources, I quickly abandoned the PC for the PlayStation 1, then the Nintendo 64.

1992: The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past – Observe and learn

My contemplative relationship with video games dates back to that early period of wonder, when I watched my older brother play The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, created by Shigeru Miyamoto for the Super Nintendo in 1992. My brother and I already shared a passion for cycling adventures, films and music; the desire for exploration, art and fiction were part of our lives. But seeing him embody the hero of an interactive epic on screen was something new. Watching him play was a new reason to spend time with my brother, and a new way of being a spectator. That’s when I began to appreciate video games for what they are: interactive fiction, capable of transporting us into new imaginary worlds, together and simultaneously.

1992: Alone in the Dark – Taking action and facing your fears

I had my first scares in a virtual world when I immersed myself in Alone in the Dark, from French studio Infogrames. Considered the first 3D survival horror game, it was one of the major inspirations for the Resident Evil series. This genre deliberately plays on our nerves, reactivating our species’ archaic fears: fear of the dark and of predators. Despite the monochrome screen and low-end sound card of our first PC, I plunged into this nightmarish universe with fear and excitement. I was scared, but something drew me in. The desire to understand the mysteries of the story was stronger than the fear of moving forward alone in the dark, equipped with only a small lantern.

Alone in the Dark made me rediscover the pleasure of playing at scaring myself, perhaps also helping to release certain unconscious fears buried in our Homo sapiens memories. Also, the pleasure of interacting with this horrific world was much more intense than the passive pleasure I felt when watching horror films with my brother and his friends. Through the recreational use of a video game, I rediscovered the benefits of interactivity and taking action: being an actor rather than a mere spectator makes events more engaging, more frightening, more complex, but also, and above all, more satisfying to undertake, understand and overcome.

1993: Syndicate – Resisting brutality and urban ugliness

The cyberpunk universe of Syndicate, created by the English studio Bullfrog Productions, was my very first experience of a semi-open world video game. It was a formative experience that shaped me into the gamer I became, and perhaps also contributed to making me the citizen I would become. I was too young to be captivated by the storylines, and I wasn’t really interested in the missions. They mainly consisted of killing and destroying, against a backdrop of power struggles between states and technology corporations. That didn’t stop me from taking part in the story, as I remained focused on my own interests: exploration, contemplation and observation.

It was the settings and characters in this story that caught my attention: a cold, ugly urban world – but one teeming with life and fascinating to observe when you are curious and mischievous. An ugliness typical of the arrogant housing estates and dormitory towns built in Western Europe in the 1950s and 1960s. Despite the brutality of this environment, I enjoyed walking the streets, observing the scenery, the vehicles, the routines of the NPCs, and contemplating this artificially recreated urban life with admiration. This curiosity was obviously rooted in my perception of the real world, acquired in my natural environment, mainly consisting of love for life, culture, and fantasy.

1993: Syndicate – Developing curiosity and resilience

Despite its ugliness and violence, the world of Syndicate was where I first experienced contemplative pleasure in a digital world. I had already experienced this feeling in my neighbourhood, nature, books, music and cinema; here I discovered a new space for contemplation, a new way of enjoying existence. I was aware that I was looking at a simple collection of cleverly arranged pixels, and yet the magic worked: I was there, with my imagination and curiosity fully awakened. It was these fundamental, formative early experiences that shaped my relationship with digital virtual worlds and now allow me to explore fiction and the territories of cyberspace with genuine pleasure.

1994: Little Big Adventure – Using frustration as a creative force

The game Little Big Adventure, developed by French studio Adeline Software, made a deep impression on me, even though I never actually played it. Our PC at the time didn’t have the SVGA colour screen needed to run it. I could only dream about it secretly, reading video game magazines. That didn’t stop me from having an indelible memory of it, quite the contrary. This frustration turned into creative energy. This off-screen realm of the inaccessible, the promises of the narrative and the visual excerpts forced me to project my imagination. Without realising it at the time, I was discovering the artistic forces at work in video games, the same forces found in all works of the mind: invented worlds capable of transporting you, inside or outside yourself, through the power of imagination alone.

1998: Unreal – Real-time 3D, virtual paradises and addictions

In 1998, as part of my studies, at a time when I was fascinated by Silicone Graphics (SGI) computers, coinciding with the launch of the International Space Station (ISS), I upgraded my PC and played Unreal, developed by Epic Games. That’s when I discovered what ‘true’ real-time 3D computer graphics were like for the general public. Captivated, I sometimes stop playing to enjoy the graphics; leaning closer to the screen, incredulous, contemplating the objects and landscapes, with the wonder of a child rediscovering the shapes of the world.

At that time, geeks like me were indeed faced with a new world: real-time 3D computer graphics were no longer just a promise, but a reality, and we were all plunging into an increasingly figurative and spectacular representation of cyberspace, with no turning back. The most vulnerable would become dependent on these alternative worlds; people who are “disappointed by reality”, emotionally deprived, with no escape, no place to wander or express themselves creatively, were – and still are – the most vulnerable. Today, as in the past, many people are sinking, without even realising it, into the abyss of these mirage worlds, responding to the siren call of the virtual paradises of video games, social networks and generative artificial intelligences.

The challenge during this formative period was therefore to learn how to maintain a vital balance between reality and geekery: to remain curious about this exciting new medium, while remaining wary of the promises of a new world based solely on the virtual. The most savvy geeks have therefore learned to navigate these new spaces with the curiosity of explorers, while keeping both feet firmly planted on the ship of reality, in order to continue living their lives and building their own stories.

1998: Half-Life | Video games and cinema – First screenshots of video games

My second aesthetic shock in a real-time 3D virtual world and my first screenshots in a video game. Also in 1998, I discovered Half-Life, a new kind of video game, based on immersive storytelling, borrowing codes from cinema, featuring a revolutionary physics engine, and detailed 3D graphics. The willingness of taking screenshots was immediate. I took a little bit of everything : place, objects, interactions, scripted sequences. A basic shooting method, a rendering a bit raw, but the big picture of Virtual Tourism was born : I found a simple method to keep memory of my virtual experiences. See the first album in the Virtual Tourism series produced from screenshots: Virtual Tourism in New Mexico.

2001 – 2004: Max Payne 1 & 2 – Action movie generator

A game brimming with pyrotechnic details that fully exploits the potential of ragdoll physics. As a fan of John Woo films since my teenage years, I enjoy playing and replaying totally improbable action scenes. Long before YouTube, during the early days of ‘Let’s Play’ videos, created by Marcus on the programme Level One on the French television channel Game One, I used a digital camcorder to capture slow-motion action sequences, showing the effects of light and objects when hit by bullets. I was thrilled. I never published these images, but the videos are still on the camcorder tapes, somewhere at my parents’ house.

2008: Fallout 3 | Art and technology – First photographs of video games

My third aesthetic shock in a virtual world, my first real experience of an open-world RPG, and my very first photographs of video game. Endless landscapes, stretching as far as the eye can see, changing atmospheric effects, NPCs reacting to your actions. The simulated universe is so consistent that it exudes an innovative beauty, at the crossroads of art and technology. I feel an irresistible urge to immortalise these landscapes. Playing on Xbox 360 at the time, it was impossible for me to take screenshots. So I spontaneously took photos with a digital camera. To my surprise, this method of shooting transformed the surface of the image, with a particular and paradoxical rendering: the game seemed more realistic, the memory of the journey more « real ». See the first album in the Virtual Tourism series, produced from real photographs: Virtual Tourism in Washington.

2010: Just Cause 2 – Horizontal and vertical exploration

The bigger map never created for 3D off-line open-world game; huge level design (exploration-oriented) on horizontal and vertical plan; jubilant physical engine sandbox like, virtuoso geographic and atmospheric effects. To sum up : the dream game to practice video games photography landscape-oriented. See the album Virtual Tourism in Island of Panau.

2011: Erwan Cario – The power of art critic

In September 2011, I discovered an article by Erwan Cario (a critic whom I have been reading since my first attempts at writing about video games), related to the photographic works of Iain Andrews. Before that, I didn’t see the point of publishing video game photos. Taking the photographs was enough for me: I captured the moment of play to better remember a nice ride in virtual spaces. These photos were just personal archives among many others, lost on my hard drive. They were even the product of a somewhat strange activity, difficult to explain, perhaps a little too geeky. An art critic had just updated my software, changing the way I saw things.

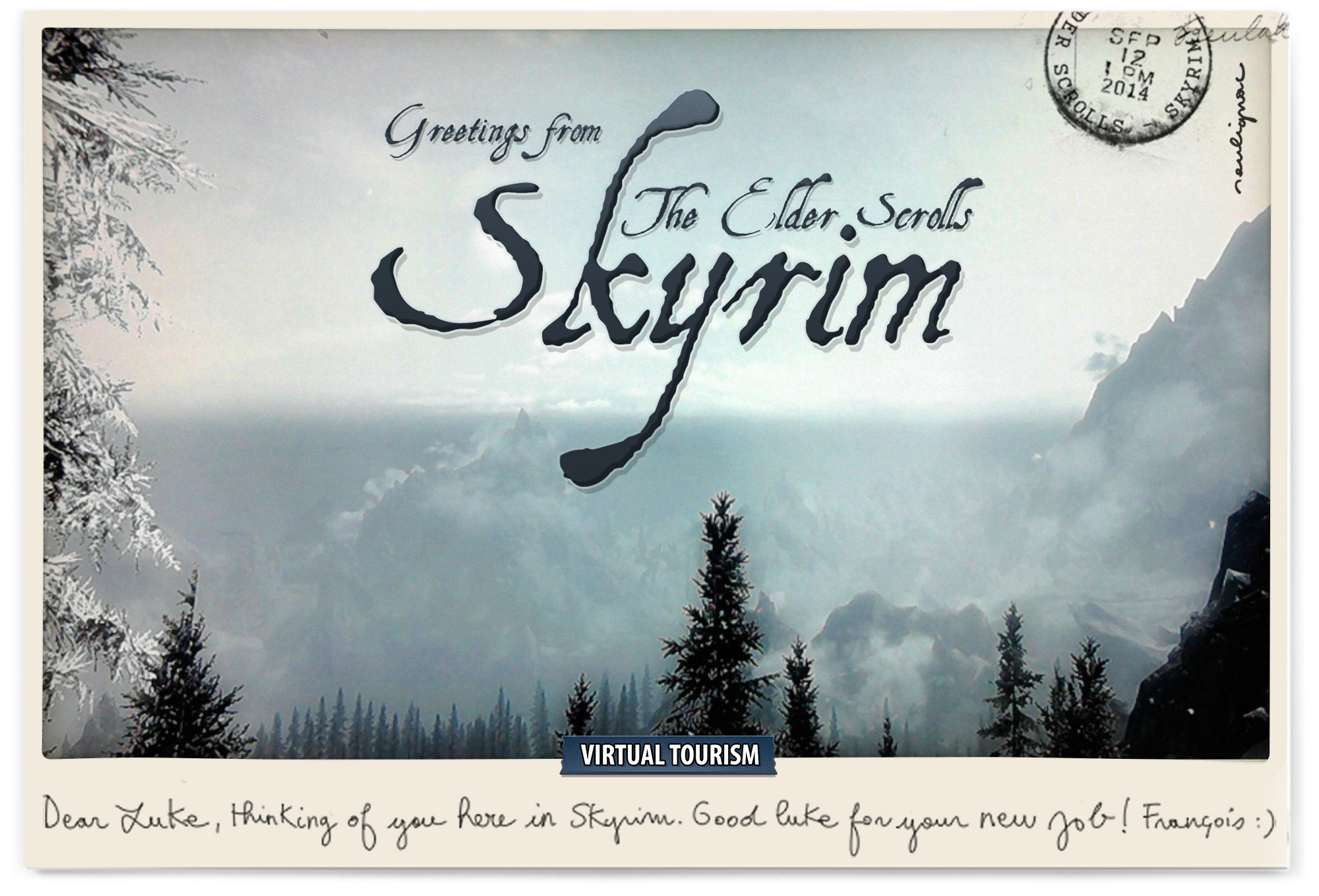

2011: Skyrim – Creation of the « Virtual Tourism » project

After discovering Erwan Cario‘s article, things quickly fell into place: I was publishing already some pictures taken during my real travel about architecture, design, location scouting; from now, within the same spirit, I could publish pictures from my virtual travel. My first published album was the virtual tour in the amazing Skyrim, certainly the bigger offline open-world game and the hugest interactive scenario I never played at this time. See the first album in the Virtual Tourism series published under this name: Virtual Tourism in Province of Skyrim.

2012: From Dust | Terraforming – Adapting to the elements and chaos

2011 saw the release of the unforgettable From Dust, a video game based on the principles of terraforming and emergent gameplay, developed by French studio Ubisoft Montpellier, then headed by Éric Chahi. Classified as a God game, the software effectively allows players to play God by helping a civilisation adapt to the elements and the consequences of their natural movements: volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, floods and tsunamis. I discovered the programme in 2012, during a period of enforced downtime, and took advantage of this exceptional situation to thoroughly explore a piece of software that I now consider to be a work of contemporary interactive art.

2013: Minecraft | Procedural generation – Getting lost to find yourself

In 2013, Sebonzenet and Vigor66, two friends who are geeks to the extreme, just like me, told me about a really cool game called Minecraft. The game had been available for a few years already, since 2009, but I had deliberately ignored it, being far too busy working on my projects in the real world. After convincing me that it was worth investing a little of my time in this simulation, I finally installed the software and joined my two friends on their ‘map’. It was an incredible place, which they had patiently built with the energy of children building sandcastles or playing at SimCity. A sequence of gradual, crescendo-like shifts was about to occur in my geeky mind, with no turning back.

2013: Minecraft | Lucid dreams and cooperation – The recreation of the world

In the beginning, we built our little farm, cooperating to secure our settlement and defend ourselves against predators. In recreating this world, our wonder was complete and constant. We eagerly experimented with the vast potential of this simulation’s sandbox, its radical interactivity. We dug fascinating, physically improbable underground tunnels, joyfully rediscovering the archaic pleasures of exploring our original caves. We built grandiose structures to climb, hang from, fall off, and then climb back up. The simulation offered what the brain allows in the phenomenon of lucid dreaming and made us relive, in a way, the major stages of our species’ evolution.

2013: Minecraft | Archaism and innovation – New forms of digital technology

Despite the scale of its programmed universe and the joys offered by the sandbox of this humble little farm, I still didn’t understand how radical and innovative Minecraft was. It was only after I decided to set off on an expedition by boat, far from this base camp, that I realised what I was dealing with: a a procedural digital world, generating a random map that appears as the player progresses.

Having no scientific training and having never experienced procedural generation in the real world, it took me a while to fully understand what it was all about. My intuitive mind, however, wasted no time in imagining the excitement that such a device could bring to an exploration project. My relationship with virtual worlds and cyberspace had just been turned upside down. Certain analogies that I had intuitively drawn up until then – between the real and virtual worlds – became archaic and irrelevant. Virtual worlds, even if they were inspired by real forms, could now take on new forms, invisible, abstract, algorithmic, beyond or below figuration, thus creating new territories, drawing new boundaries and consequently imposing on us a new prism of interpretation and a new relationship with the world.

2013: Minecraft | Travelogue – The fear of uprooting

As I explored the world of Minecraft, emotions usually associated with reality were triggered in me: the anxiety of preparing for the trip; the loneliness felt after departure; the possibility of getting lost during the expedition or losing track of my travelling companions. Less well known is the fear of not finding your way back, of not being able to find yourself again – or worse, not being recognised upon your return, becoming a victim of permanent uprooting. These were very real emotions which, coincidentally, were the first signs of what I would feel shortly afterwards, during my actual trips to China (2014-2019) and Vietnam (2019-2021).

2014: BeamNG.drive | Accidentology – Learning while having fun

Like many children, I loved playing with toy cars, inventing adventures and stunts. I particularly enjoyed playing with Crash Dummies, toys inspired by real crash tests on commercial vehicles. Both fun and educational, these toys succeeded in conveying the real physical consequences of a road accident. In 2014, a German studio turned this little boy’s fantasy into digital reality with the BeamNG physics engine. A little technological and aesthetic gem, a dynamic vehicle simulator with soft-body physics capable of doing just about anything. Watch the video Virtual Tourism by car.

2016: Just Cause 3 – Car chase generator

In 2016, with Avalanche Studios’ Just Cause 3, I rediscovered the joys of contemplating a simulated world. It was the physics engine developed by the Swedish studio that caught my attention. The programme was so satisfying that I captured slow-motion sequences of explosions. The software allows for the destruction of large structures, such as bridges – a technical feat for the time, especially in such a vast programmed universe. With its randomly generated car chases and fluid stunts, the Just Cause series has become, in my eyes, the most perfect digital representation of a childhood classic: playing with toy cars. Watch the video Virtual Tourism in Medici Archipelago.

2016 – 2020: In-game photography is mainstream

The games released in the late 2010s were numerous and rich in worlds to explore. Most open-world games now offer a built-in photography mode, catering to fans of the new popular art form that video game photography has become, now officially called In-game photography or Virtual photography.

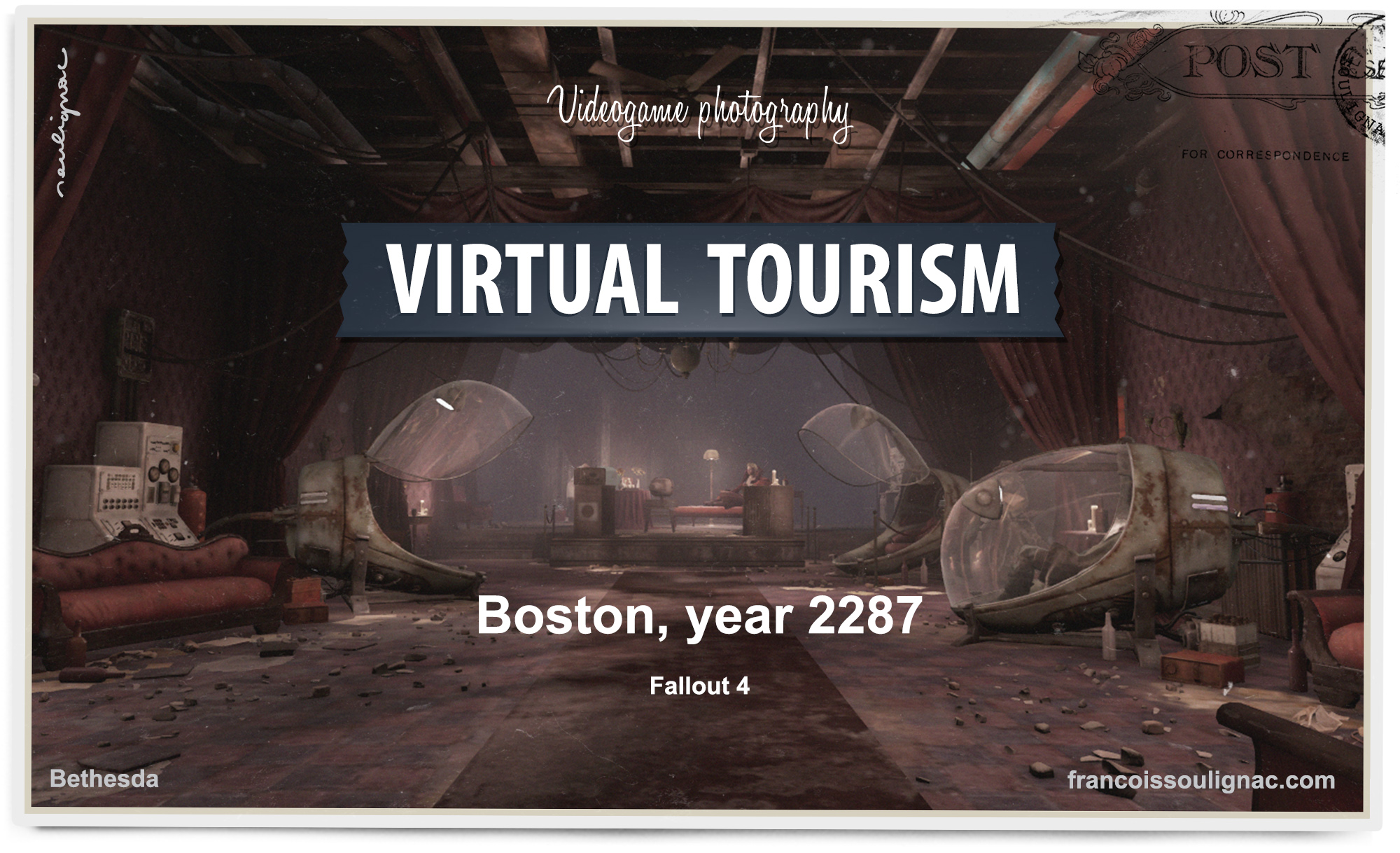

2016 – 2020: Urbex – Virtual urban exploration

At the end of the 2010s, after deserting virtual worlds for a few years – already busy exploring new territories IRL – I resumed my virtual exploration, starting with urban exploration in the Boston of Fallout 4; then after in Wasteland’s desert of Mad Max, the San Francisco of Watch Dog 2, the city of Columbia in Bioshock Infinite, in the miraculous Middle Ages recreated by Polish studio CD Projekt, The Witcher 3; as well as in its very ambitious (perhaps overly) Cyberpunk 2077 – a virtual world and a simulation that did not leave me indifferent.

2018: Rediscovering the past, imagining the future

Starting in 2018, after acquiring a PS4 Pro sold by a friend who ‘wanted to get rid of it because he was spending his life on it,’ I happily lost myself for a long time in Ancient Egypt of Assassin’s Creed Origins and its visionary “Discovery Tour” DLC; representing a Ubisoft’s major contribution to the creation of interactive documentary experiences and in the development of new methods for knowledge acquisition. I loved exploring the mysterious universe of Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End, a true ode to travel and the finest contemporary representative of adventure entertainment. I then discovered with great interest the dark and visionary universes of Detroit: Become Human, by French studio Quantic Dream, and Metro Exodus, by the Ukrainian studio A4Games.

2020: The Soulignac Brothers – Reconnecting despite restrictions

In December 2020, in the midst of a global pandemic and severe travel restrictions, my brother and I were living 10,000 km apart. He was in Paris, while I was in Saigon (Vietnam). We began to wonder how we might see each other for the holidays despite these constraints. In previous years, I would usually travel physically for the holidays, by plane, thereby generating an excessive and unreasonable amount of carbon emissions. We could also have chosen to connect through voice or video calls. But since we both shared a passion for video games and new technologies, and had previously collaborated on the GTA 4 episode of the Virtual Tourism series (Los Angeles vs Los Santos), we simply decided to meet up in our favorite video game: Red Dead Redemption 2.

2025: Cyberspace – New territories

The Virtual Tourism series has always been a very solitary project. In 2020, it became a family affair, a collaborative project between brothers who share the same passion. The goal was simple: to get together despite travel restrictions, chat, have fun and try to keep a tangible memory of this moment. This idea then turned into a video project, inspired by the pioneers of the genre Machinima, which can be found on our YouTube channel. From 2025 onwards, the project will resume and become an experimental writing project on the experience of virtual travel in the broadest sense, extended to the continent of cyberspace.

2026: Cyberspace – New rituals

Today, the Virtual Tourism project has become a personal writing and research project that attempts to document the emergence of new rituals within digital virtual worlds. Presented now as a series of logbooks, this project is always evolving, shaped by the shifting boundaries of cyberspace and ongoing discussions about the metaverse’s possibilities. Learn more about the collective The Soulignac Brothers and discover all our travel.

About the process

I hate travelling and explorers

With a camera at my disposal, I simply walk into the decor of video games which offer open worlds. I explicitly do this without paying attention to the context (off-mission). I wander around these wide digital open spaces, solely to appreciate the work produced by graphic designers and developers. I then start searching for the best spot where I can take a picture with the most suitable view, location, frame and ideal moment. Those visuals, which are mainly focused on landscapes, are a way to keep memory of my excursions in cyberspace and the metaverse. They also often reveal empty or abandoned areas of gameplay, places that are usually ignored or overlooked by players focused on scoring and performance.

Digital poetry

My intention is neither utilitarian, journalistic nor scientific. My approach is purely poetic; I express my travel impressions through images or words. In a video game, I keep my real photographic habits. I live my journey without being riveted behind my lens. Sometimes I don’t even have the time – or the desire – to take photographs. In the masterpiece Red Dead Redemption 1, released in 2010 by American studio Rockstar Games, I simply didn’t have the “photo reflex”, too absorbed by its storyline and universe.

Exploration with no constraints

Also, some programs do not lend themselves well to the exercise: games in the third person or certain graphic universes do not allow me to obtain satisfactory results. My priority is to enjoy the game, to contemplate its programmed universe and to take a few pictures. My goal is not to build an useful guide, with practical map, good plan and reviews. If you are interested by this way to play – and to write – you must read the articles of the French journalist Olivier Seguret, named Tourisme virtuel (in French).

Creative tourism

The title of the series “Virtual Tourism” refers to my way of playing. I’m not a scoring enthusiast, I consider video games as a rich cultural product, whose sole purpose is not to entertain. I love to play games, of course, but my pleasure is doubled when a deep scenario unfolds and the possibility of getting out of it is offered. Then I like to get lost in the map, test the limits of the program, reach hard-to-reach areas, be surprised by an event, dream, fiction, imagine the designers’ development techniques. In short, I’m a bit like those tourists who visit a country without any planning. Once in the program, I embark on a deep, creative, limitless – or almost limitless – exploration armed with my imagination and a camera.

Search Engine Optimization

The titles of Virtual Tourism posts do not have the name of the game but the names of the places where the story of the game takes place. This little detail of nomenclature had an unexpected effect on search engines: Google’s algorithms did not differentiate between real and virtual places, so my photographs quickly cohabited with the screenshot of real virtual tour software. Perhaps more interesting is Journey’s intrusion when an Internet user searches for photographs of unknown desert.

Emergent gameplay

Today, as an aesthete-gamer passionate by emergent gameplay, I’m mainly focused on openworld-sandbox games. Not only because they are at the forefront of technological innovation and writing methods in the field of new media, but also because they simply meet my needs: time and space are open there, the ideal conditions for a contemplative video game photographer.

Shooting methods

Method 1: Photographs of video games

From 2008 onwards, I started this series by taking real photographs rather than screenshots. This method sublimated the image and made the texture of the screen visible, allowing me to capture the technical features of the equipment of that time, in anticipation of the major changes soon to come in how content was broadcast. The aim was to produce the final piece while taking the picture. The initial photos were originally taken in high definition and were eventually reduced to a smaller size before being posted online. The pictures online were either left in their original state or moderately altered: a little cropping and editing (brightness, saturation of colours). This method of shooting had two advantages: when in front of the screen, the moment the picture was taken, the camera reinterpreted the pixels. This created a “smoothing” effect on the surface, which eradicated the sometimes too brutal aspect of some decors due to the work of current 3D engines. Finally, when the images were cropped, the visibility of polygons was naturally reduced. The finishing result allowed me to acquire a “new” image—one which was embellished and beautified, yet nonetheless remained loyal to the original game.

Method 2: Screen’ captures and logbooks

From 2015 onwards, I began favouring HD screenshots in order to pay a more faithful tribute to the work of the designers, especially in Fallout 4, Mad Max and Assassin’s Creed Origins. From 2016 onwards, video capture will be used to showcase the physics engines of BeamNG.drive and Just Cause 3. In 2020, the creation of the collaborative project by The Soulignac Brothers systematised the use of video capture, in order to showcase the programmed worlds of Red Dead Redemption 2, Metro Exodus, Detroit: Become Human and Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End. The Virtual Tourism project, now less focused on the pictorial work of capturing images, has become a work of writing and testimony, a series of logbooks describing my impressions of travels on the continent of cyberspace.

Postcards from virtual worlds

I take in-game pictures to keep tangible memories of my virtual experiences. During these trips, I sometimes send postcards to share my memories and connect with people. Read more.

Albums

- USA, year 1899 (RDR 2)

- Uncharted Territories (Uncharted 4)

- Detroit, year 2038 (DBH)

- Russia, year 2035 (Metro Exodus)

- Night City (Cyberpunk 2077)

- Ancient Egypt (Assassin’s Creed)

- Boston, year 2287 (Fallout 4)

- Desert of Wasteland (Mad Max)

- Medici Archipelago (Just Cause 3)

- Tourism by car (BeamNG.drive)

- Los Angeles (Grand Theft Auto 5)

- Los Santos (Grand Theft Auto 5)

- Rook Islands (Far Cry 3)

- Sao Paulo (Max Payne 3)

- Hong Kong (Sleeping Dogs)

- Province of Skyrim (Skyrim)

- Island Nation of Panau (Just Cause 2)

- Washington, D.C., year 2277 (Fallout 3)

- Mountains & Desert (Journey)

- City of Haventon (I Am Alive)

- Arkham City (Batman: Arkham City)

- New-Mexico (Half-Life)

Virtual Tourism on Press

© 2011-2026 François Soulignac | Virtual Tourism – Video games photography / In-game photography – Creative walks in cyberspace.